— by John Lewis —

My strongest and deepest attraction to music was through jazz, and I think it was instantaneous. Therefore I have always listened to, thought about, composed, and played music through jazz. Some of the features of jazz which I found most attractive were swing, blues inflection, tension, energy, and the variety offered by improvisation.

My first memorable contact with J.S. Bach’s music was a radio performance by the Philadelphia Orchestra of the D minor Tocatta and Fugue, arranged and conducted by Leopold Stokowsky. I was later impressed by a radio performance of the slow movement of the orchestral suite in D major – popularly known as the “Air on the G String.” In the “AIR on the G String,” I heard wonderful possibilities for improvisation using the wonderful, logical chord progression and using the melodic line as a cantus firmus as a basis for improvisation. Not long after hearing the “Air,” I heard a marvelous treatment of “The Sidewalks of New York” by Duke Ellington: in the second chorus he had the melodic line played by and embellished by trombonist Joe Nanton, and had the secondary harmonized line played by the saxophones – for me it is still one of the most wonderful counterpuntal gems I know of. It suggested to me Bach’s Chorale Prelude formula.

Another great experience for me was discovering Bach’s intense harmonic chromaticism. The later eighteenth and nineteenth century great European composers did not impress me as much as, for example, Bach’s treatment of “The Old Year Has Now Passed Away” as a Chorale Prelude. I later made a transcription of that work for the Modern Jazz Quartet.

The greatest influence on my work for the MJQ has been: simple imitation. This occurs a great deal in my accompaniment to both the themes and the improvised sections that we play. Examples are in the treatment of Milt Jackson’s “Ralph’s New Blues” and in “Cortege” a composition of mine written for “No Sun in Venice,” a film score.

More distinct influences of Bach on my work have been his elaborate forms of imitation, such as the invention – as a piano student, I enjoyed playing Bach’s two and three part inventions. My first counterpuntal piece for the MJQ was an invention enitled “Vendome.” With that piece, I experienced and found I had to solve the problem of creating material that would have the feeling of swing. “Vendome” did not have this, particularly in our first recording of the composition; it was my first effort, and I still had much to learn. My colleagues in the MJQ, however, gave me their best effort. We later recorded “Vendome” with the Swingle Singers in a more successful performance. One of the principal differences for us (the MJQ) between Bach’s forms and those we were accustomed to were his use primarily of sectional forms, and our use of the song forms (ABA, ABAC). A more successful use of one of the elaborate forms was “Concorde,” also recorded by the MJQ. “Concorde” is my use of the Fugue form based on Bach’s influence. The theme lends itself more easily to the jazz feeling of swing. Still, the episodes of “Vendome” lend themselves to improvisation, and all three pitch instruments have an opportunity to participate in the performance. Other Fugues are “Alexander’s Fugue” for MJQ and the Swingle Singers – it was designed in improvised sections for the MJQ which due to poor remixing were practically eliminated with respect to the balance of volume between the MJQ and the singers; “Little David’s Fugue” – it did not fare much better with respect to balance, although the performances by the Swingles and the MJQ were wonderful; the Third Fugue included in the same album was “Three Windows,” from “No Sun in Venice,” which uses 3 principal ideas rather than one, as in the aforementioned Fugues. The use of the Canon form takes place in “La Cantratice,” from a suite entitled “The Comedy” by the MJQ and in “Jazz Ostinato,” for MJQ and orchestra.

In a composition entitled England’s Carol, which is based on the English Christmas Carol, “God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen,” I made use of J.S. Bach’s Chorale Prelude idea, with alterations to the design to accomodate improvisation. In addition to original compositions influenced by J.S. Bach, some transcriptions were also made of

- “Sleepers Awake” – subtitled “Rise Up in the Morning”

- “Jesus Joy of Man’s Destiny” – subtitled “Precious Joy”

- Fugue in D minor from the Clavier Buechlein – subtitled “Don’t Stop This Train”

- Prelude #8 from W. T. C. – subtitled “Tears from the Children” (This was also recorded in a two piano arrangement with the great pianist Hank Jones.)

- “The Old Year Has Now Passed Away” – subtitled “Regret?”

- “Air on the G string” – one of my earliest favorites of J.S.Bach, it was transcribed for MJQ and the Swingle Singers by Ward Swingle and myself. This performance contains improvised sections using the Cantus Firmus idea – the first section by Milt Jackson, and the second section by myself.

- The Ricercare from ‘The Musical Offering’ – another transcription for MJQ and the Swingle Singers

- Finally, I made a transcription of the Fugue in A minor from the book of Little Preludes and Fugues, performed and recorded by the MJQ and the guitarist Laurindo Almeida.

I must say that the counterpuntal music of J.S. Bach has had a great influence on my work for the MJQ.

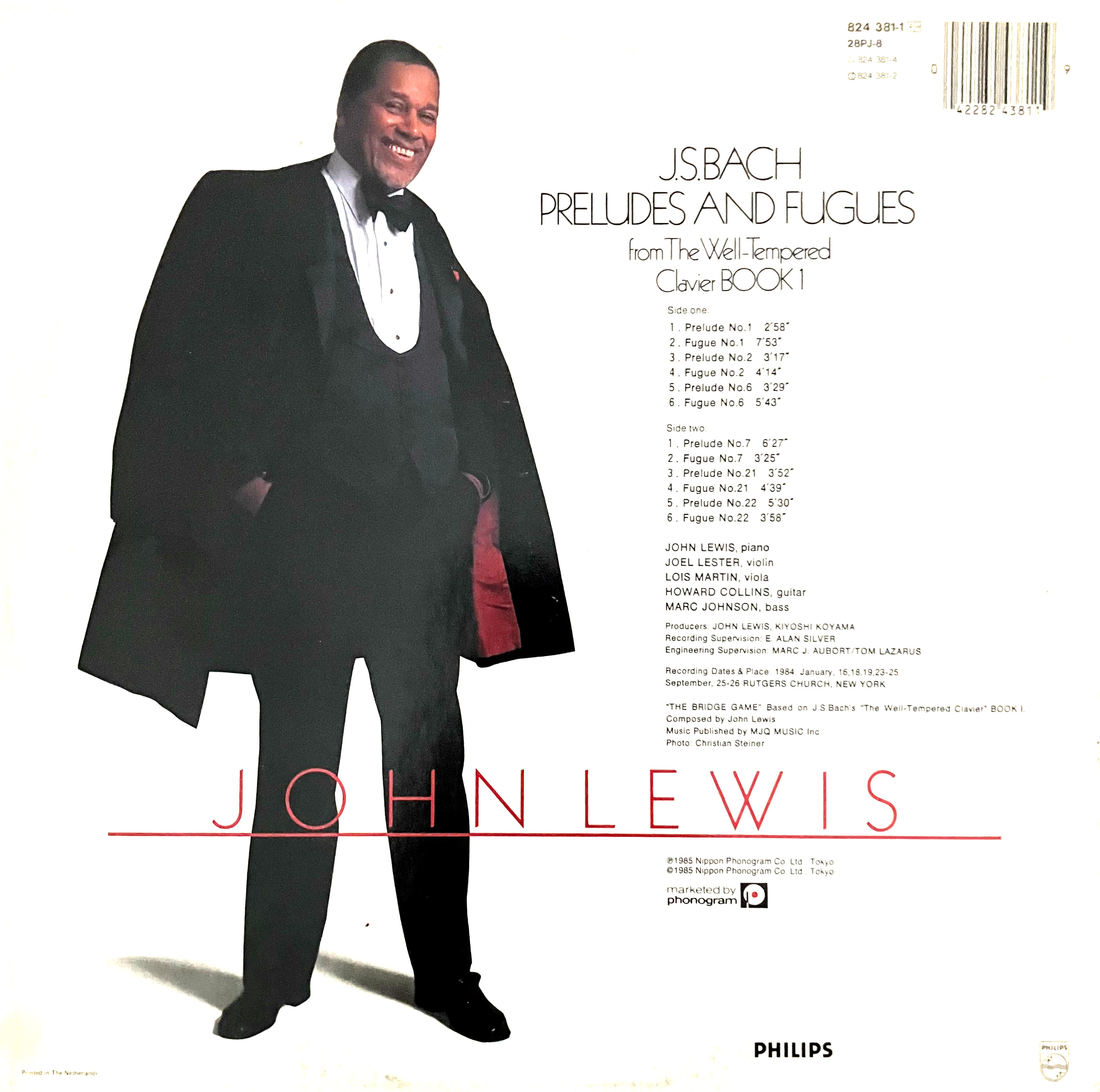

I have this year undertaken, with some trepidation, a project of recording the Preludes and Fugues from the Well Tempered Clavier Book I, for the Japanese record company Nippon Phonogram. I say with trepidation because this project has demanded a great deal of preparation on my part, both in the form of piano practice and in the form of compositional work. I have recorded the Preludes as solo pieces, with some of them including improvised sections as well as a personal phrasing of the original material. In the Fugues, I decided to use a different instrument for each voice. For the three voice Fugues I have used piano, guitar, and contrabass. For the four voice Fugues I added a violin, and for the five voice Fugues I added both the violin and the viola. All of the Fugues have improvised sections, which are performed by myself.

While all of the great masters of Western music have had a tremendously enriching effect on my life, it is J.S. Bach’s influence which has probably been most in evidence in my writing and performance.

John Lewis was born on May 5, 1920, in LaGrange, Illinois, but was brought up in Albuquerque, New Mexico. His interest in music began early; he began studying piano at age 7. Jazz Musicians who played in Albuquerque, such as the great tenor saxophonist Lester Young, made a great impression on Lewis during his childhood years.

All throughout his study of anthropology at the University of New Mexico, music remained an important part of Lewis’ life. After serving in the army during W.W.II, Lewis pursued music, playing and arranging for the Dizzy Gillespie orchestra, and also playing with Charlie Parker and Miles Davis. Lewis studied theory and composition at the Manhattan School of music; the advanced studies he completed there – with an M.B.A. – familiarized him with European orchestral repertoire and enabled him to acheive one of the most ground-breaking expansions of the scope of jazz music to date.

With the three other ex-members of Dizzy Gillespie’s rhythm section, vibraharpist Milt Jackson, bassist Ray Brown, and drummer Kenny Clarke, Lewis formed a quartet. With the substitutions of Percy Heath on bass and Connie Kay on Drums, this quartet became the now over 30-year-old institution known the world over as the Modern Jazz Quartet.

A prolific composer and an effortless manipulator of form, John Lewis has brought to the MJQ an unerring musical vision. The compositional and improvisational integrity he gave the group contributed to the MJQ’s rise to a position of prime importance in the history of jazz. Lewis, as musical director for the MJQ, has written and arranged nearly all of the music on the group’s 40 plus albums. The unique quality of his work, which draws on the best of jazz and European musical tradition, has earned him a place among those rare few who can truly be called jazz composers: in the words of noted jazz critic-historian Leonard Feather, Lewis “...stands in the jazz pantheon with the likes of Duke Ellington. Lewis is one of the most brilliant minds ever applied to jazz...” Lewis’s composition for the MJQ has both the reflective, complex contrapuntal quality of the European tradition and the hard-swinging blues sounds fundamental to jazz.

Lewis has written for a great variety of ensembles, ranging from the Modern Jazz Quartet to his unique creation during the 1960’s, the Orchestra USA. Lewis’s interest in musical forms and colors beyond the physical limitations of traditional jazz instrumentations led him to form and direct the Orchestra USA in 1962 to 1966. An aggregate of virtuoso musicians, the Orchestra USA was a unique vehicle for new American composition; it was the first orchestral ensemble dedicated to performing with equal beauty and aplomb all American music, whether jazz-influenced, European-influenced, or, as was often the case, a combination of both influences.

Desiring to vary and expand the settings for his work, Lewis successfully composed for diverse groups – such as string quartets and full orchestras – and for theatre, ballet, and motion pictures. He was the first jazz composer to write a major motion picture jazz score: his scores for the films “Odds Against Tomorrow” (directed by Robert Wise) and “No Sun in Venice” (directed by Roger Vadim) have been singled out for their excellence. In addition, his incidental music for William Inge’s play “Natural Affection,” and for numerous TV series and film documentaries received critical acclaim.

Lewis has been a very active recording artist apart from the MJQ collaboration. Since the early srxties, he has recorded numerous albums for Atlantic records and has had great success recording solo work as well. His 1961 solo recording, “John Lewis Piano” was pronounced gold medal record of the year in Japan. He has recorded almost a dozen albums since then, collaborations with such artists as Hank Jones, Lew Tabackin, and Bobby Hutcherson, Svend Asmussen, and Helen Merrill among others.

Lewis has also served as musical consultant for the famous Monterey Jazz Festival every year from 1955 to 1982. He has served education as professor of music at City College in New York for the past 8 years. In recent years, John Lewis has received the highest recognition of the academic world, being awarded with several honorary Doctorates of Music. Since 1980, he has received Honorary Doctorates from the University of New Mexico, from Columbia College in Chicago, and from the New England Conservatory of Music, the United States’ oldest music conservatory.