When assembling the program for

In a Mellotone

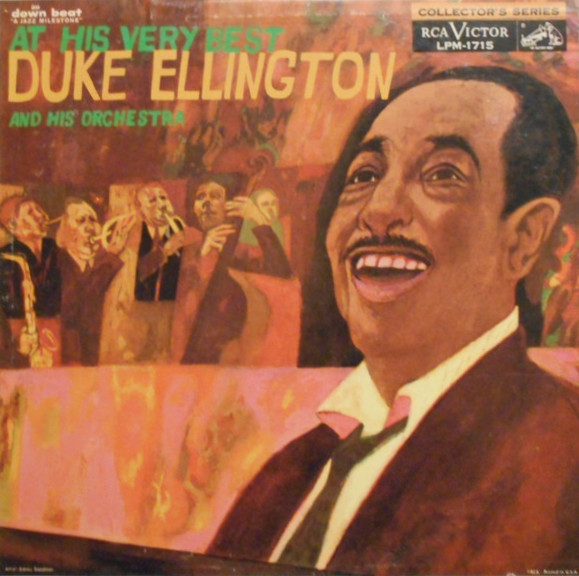

(RCA Victor LPM-1364), a collection of Ellington recordings from 1940-1942, I noted that we had omitted several vital selections in our desire to collate only those recordings that had not previously been available on L.P. Since then, it has become increasingly evident that even 10” L.P.s have now become collectors’ items, and so we are including in this Ellington album several of the 1940-42 achievements that should never be allowed to go out of circulation.

The personnel of the band on the first side, unless otherwise noted, consists of: Trumpets — Wallace Jones, Cootie Williams, Rex Stewart; Trombones — Joe “Tricky Sam” Nanton, Lawrence Brown, Juan Tizol; Clarinet — Barney Bigard; Saxophones — Otto Hardwick, Johnny Hodges, altos; Ben Webster, tenor; Harry Carney, baritone; Rhythm Section — Fred Guy, guitar; Sonny Greer, drums; Jimmy Blanton, bass; Duke Ellington, piano.

Side 1

Jack the Bear (March 6, 1940)

This Ellington composition and arrangement was, noted Leonard Feather, “the first band number written to present Jimmy Blanton whom Ellington had discovered a few months before and who, until his tragic death in 1942, was to revolutionize the concept of the use of his instrument in jazz, raising it from the level of a rhythm instrument to one with melodic solo potentialities.” The soloists are: Blanton, Ellington, Bigard, Williams, Bigard again, Carney, Tricky Sam Nanton and Blanton.

Concerto for Cootie (March 15, 1940)

Later called Do Nothin’ Till You Hear from Me, Concerto for Cootie (Williams) is the subject of a detailed analysis in André Hodeir’s Jazz: Its Evolution and Essence (Grove Press). Writes Hodeir: “Concerto for Cootie is a masterpiece ... because it doesn’t have that slight touch of softness which is enough to make so many other deserving records insipid ... because the musical substance of it is so rich that not for an instant does the listener have an impression of monotony ... We have here a real concerto in which the orchestra is not a simple background, in which the soloist doesn’t waste his time in technical acrobatics or in gratuitous effects. Both have something to say, they say it well, and what they say is beautiful. Finally, Concerto for Cootie is a masterpiece because what the orchestra says is the indispensable complement to what the soloist says; because nothing is out of place or superfluous in it; and because the composition thus attains unity.”

Harlem Air Shaft (July 22, 1940)

“So much goes on in a Harlem air shaft,” said Duke once. “You hear fights, you smell dinner, you hear people making love. You hear intimate gossip floating down. You hear the radio. An air shaft is one great big loudspeaker. You see your neighbors’ laundry. You hear the janitor’s dogs. The man upstairs’ aerial falls down and breaks your window. You smell coffee. A wonderful thing, that smell. An air shaft has got every contrast. One guy is cooking dried fish and rice and another guy’s got a great big turkey ... You hear people praying, fighting, snoring. Jitterbugs are jumping up and down always over you, never below you ... I tried to put all that in Harlem Air Shaft.” The soloists are: Nanton, Williams, Bigard, Cootie, and Bigard again.

Across the Track Blues (October 28, 1940)

Many New Yorkers have come to know this intimately as the theme for John Wilson’s excellent WQXP series, “The World of Jazz.” Soloists are: Blanton and Ellington, Bigard, Stewart, Brown, Barney again.

Chloe (Song of the Swamp) (October 28, 1940)

A song that had rarely, if ever, before connoted jazz of any kind came in this Ellington treatment to sound as if it were an Ellington original. The solos are by Nanton, Bigard, Brown, Blanton, Williams and Webster.

Royal Garden Blues (September 3, 1946)

By this time, the Ellington reeds were Jimmy Hamilton, Russell Procope, A1 Sears, Hodges and Carney. Trumpets were Shelton Hemphill, Ray Nance, Harold

Baker, Taft Jordan, William “Cat” Anderson and Francis Williams. Trombones were Lawrence Brown, Claude Jones and Wilbur De Paris. In the rhythm section were Duke, Freddie Guy, Oscar Pettiford and Sonny Greer. Royal Garden Blues is a jazz tune with a relatively long tradition of performance; but after being placed in Ellington perspective, the song sounds fresher and more intriguing to me than ever before — or since. Soloists are Nance, Brown, Anderson.

Warm Valley (October 17, 1940)

The song is a setting for Johnny Hodges, with a trumpet solo by Cootie Williams. This kind of material is exactly fitted to Hodges’ sensuously lyrical romanticism.

Ko-Ko (March 6, 1940)

No one record can totally summarize the 1940-44 Ellington period, but this comes close in the thoroughly personal sound of the voicings; the quality of the work as a unit; the way the solos are integrated into the texture of the work as a whole; and the unique combination of sophisticatior and joyful élan that characterize Ellington and his orchestra at their most exhilarating. Ko-Ko also indicates several of the ways — harmonic especially — in which Ellington presaged a goodly portion of current “modern jazz” writing. As Miles Davis once said to Leonard Feather during a “Blindfold Test”: “I think all the musicians should get together one certain day and get down on their knees and thank Duke.”

Side 2

Black, Brown, and Beige (December 11 and 12, 1944) In “The Future of Form in Jazz” (Saturday Review, January 12, 1957), Gunther Schuller wrote: “The idea of extending or enlarging musical form is not a new one in jazz. By the middle Thirties Duke Ellington had already made two attempts to break beyond the confines of the ten-inch disc with his Creole Rhapsody of 1931, and the twelve-minute Reminiscing in Tempo (1935). An even more ambitious Ellington attempt to explore the possibilities of large-scale jazz works came in 1943 when he wrote Black, Brown, and Beige: Tone Parallel to The American Negro.

The premiere performance was at Carnegie Hall January 23, 1943. The concert was to be the first of an annual series that many remember as among the most stimulating jazz experiences of their lives. The work originally ran 50 minutes, and only excerpts were recorded for Victor. These excerpts form the large percentage of the second side of this album.

The reeds on these recordings were: Hamilton, Hardwick, Hodges, Sears, Carney. Trumpets were Hemphill, Nance, Jordan, Anderson. Trombones were Brown, Jones, Nanton. The rhythm section had Duke, Guy, Greer, and the late Alvin “Junior” Raglin, bass.

On Work Song, the opening section, solos are by Harry Carney and Tricky Sam Nanton with Otto Hardwick’s alto leading the spiritual-like theme that ends the section with promises. “That’s the way it should end,” said Ellington at the time of the concert. “How can it be tied and boxed and stored away when there’s so much more to do? These unfinished endings are reality.” So is the mockingly perceptive humor of Tricky Sam.

As described in the notes to the original recording, the beginning of Come Sunday, with Ray Nance on violin, depicts “the movement inside and outside of the church” while the workers stand outside, watch and listen, but are not admitted. “The theme develops to the time when the workers have a church of their own,” at which point Johnny Hodges’ almost translucent solo is heard.

The Blues includes a tenor solo by A1 Sears, but is best remembered for Duke’s lyrics. The singer is Joya Sherrill:

“The Blues ...

The Blues ain’t

The Blues ain’t nothin’ but a cold gray day,

And all night long it stays that way.

Ain’t somethin’ that leaves you alone,

Ain’t nothin’ I want to call my own,

Ain’t somethin’ with sense enough to get

up and go.

Ain’t nothin’ like nothin’ I know.

The Blues ...

The Blues don’t ...

The Blues don’t know nobody as a friend,

Ain’t been nowhere where they’re welcome

back again...

Low ... ugly ... mean ... Blues! [Tenor solo]

The Blues ain’t somethin’ that you

sing in rhyme,

The Blues ain’t nothin’ but a dark

cloud markin’ time.

The Blues is a one-way ticket from

your love to nowhere,

The Blues ain’t nothin’ but a black

crepe veil ready-to-wear.

Sighing ... Crying ...

Feel most like dying ...

The Blues ain’t nothin’ ...

The Blues ain’t ...

The Blues ...’ *

The first of the Three Dances is West Indian Dance, dedicated “to the valorous deeds of the seven hundred free Haitians of the famed Fontages Legion who came to aid the Americans at the siege of Savannah in the Revolutionary War.”

Emancipation Celebration (continues the Duke) “describes the mixture of joyfulness on the part of the young people, and the bewilderment of the old on that great gettin’ up mornin’.’ Youth exultantly anticipated a lifetime of glorious freedom: but age, after long, weary years of servitude suddenly found itself ironically free to go — but where? The initial strain captures the spirit of youth’s ‘graceful awkwardness and abandon’ in the solos of Jordan, Nanton and Raglin.”

Sugar Hill Penthouse (also known as Creamy Brown) is described by Ellington as “representative of the atmosphere of a Sugar Hill penthouse in Harlem which cannot be understood nor appreciated unless one has lived there.” In characteristic Ellington prose, he added: “If you ever sat on a beautful magenta cloud overlooking New York City, you were on Sugar Hill.”

Creole Love Call (October 26, 1927)

Transblucency

(A Blue Fog That You Can Almost See Through) (July 9, 1946)

The album closes with two examples of another way in which Ellington was a significant direction-indicator in jazz — the use of the voice as an additional instrument in the orchestra. Only recently have modern jazz composers begun again to explore the possibilities of the almost fully instrumentalized voice, and it seems quite likely that as more attempts are made to broaden and deepen the texture of jazz compositions, more work along this line will be under taken. Ellington was doing this at least as far back as October 26, 1927, when Creole Love Call was made The voice is Adelaide Hall’s, and she sounds like a particularly sensitive growl trumpeter. The actual trumpet is Bubber Miley and the clarinet is Rudy Jackson.

By July 9, 1946, and Transblucency, Ellington had experimented a number of times with the voice-as-instrument, and his own over-all use of his band as an instrument had, of course, developed hugely. The voice here is Kay Davis’ and she is much more central and closely involved a figure in the evolution of the work than Adelaide Hall had been nineteen years before. Soloists are Brown, with whom Miss Davis also plays a duet, and Ellington. She also plays alongside Hamilton’s clarinet. Subtitle of the song, by the way, is “A blue fog that you can almost see through,” and it’s a development of Blue Light, recorded in 1938. Personnel is the same as on Royal Garden Blues, with the addition of Nanton on trombone.

As often happens with men who have been producing for a long time, Duke is somewhat taken for granted by many of us. But look through the catalog some time, and listen once more to some of the recordings he’s made, the pieces he’s written, the always modern influence he has been. The man — for all his masks in public — has left a nonpareil body of music of which a sizable amount is likely to last beyond our reckoning.

—Nat Hentoff, Co-editor of

The Jazz Revue

* Reprinted, by permission of Tempo Music, Inc.

© Radio Corporation of America, 1959

|

LPM-1715

|

|

PRINTED IN U.S.A.

|